The end of feudalism and the founding of the Italian nation state

The previous article, How did Puglia’s Masserie develop after the Middle Ages?, explained how and when the rural Puglia that we can still discover today came into being.

Until the unification of Italy in 1861, Puglia remained a pawn in the conflicts between the great European powers. The great plague of 1656 devastated the entire Kingdom of Naples and, apart from a period of economic recovery in the 18th century, Puglia remained mired in poverty and backwardness. Neither the Habsburgs nor the Spanish Bourbons pursued a policy of development and promotion in their southern Italian possessions.

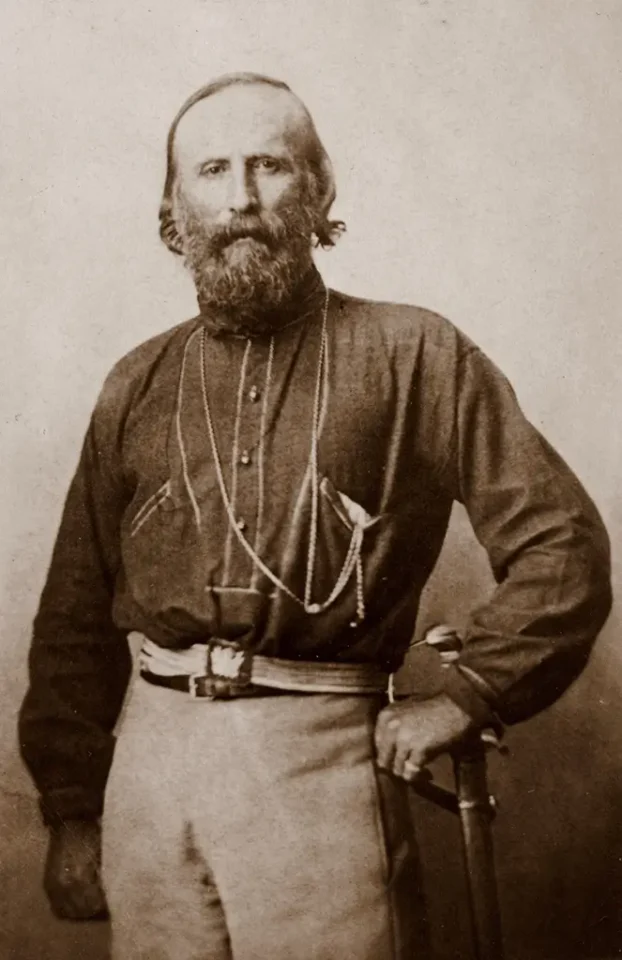

The overthrow of the Spanish-Bourbon dynasty by the revolutionary troops of Giuseppe Garibaldi finally put an end to centuries of foreign domination. The territory of the former Kingdom of Naples was incorporated into the newly created Kingdom of Italy in 1861: the birth of the first modern Italian nation state under the rule of the House of Savoy.

Guiseppe Garibaldi 1861

Photo: Library of Congress, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

However, it was Napoleon Bonaparte who gave the first impetus to modernisation and progress in Puglia: in 1806, after the invasion of French troops, he enthroned his brother Joseph Bonaparte as King of Naples. Dissatisfied with him, however, he deported him to Spain in 1808 and installed his brother-in-law Joachim Murat as king.

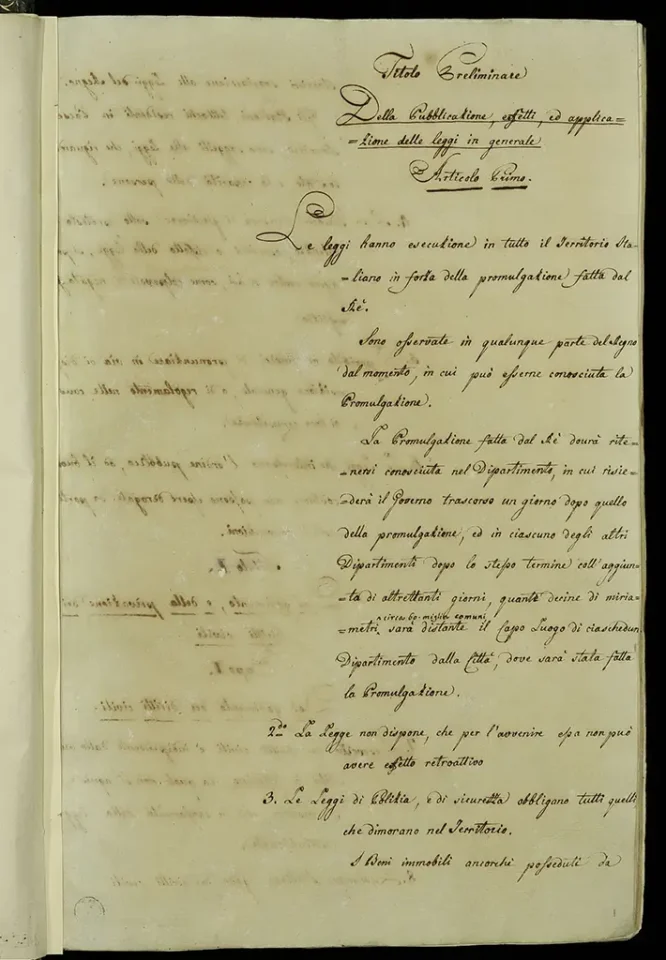

Although it was another period of occupation, southern Italy owes him the establishment of a modern administration and the abolition of the feudal structures that had existed until then. In 1809, Murat introduced the Napoleonic Code, which for the first time legalised divorce, civil marriage and adoption. In the same year, a law was passed ordering the closure of monasteries throughout the kingdom and the transfer of property to the state. The establishment of a land registry, the introduction of a land tax, the liberalisation of trade and the stimulation of modern construction all led to a strong push towards enlightenment and modernity.

A few years later, however, the Napoleonic era was over and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, established by the Congress of Vienna, fell to the Spanish Bourbons in 1816.

Codice civile by Napoleone Bonaparte in an italian Edition

Photo: Archivio di Stato di Milano, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Gangs of bandits and slave hunters as a symptom of the centuries-long power vacuum

For centuries, until well into the 19th century, the Apulian countryside was plagued by bands of robbers and slave hunters of various stripes. Not only did foreign powers take advantage of the unstable power relations in this strategically important region, but the lack of development in the interior and the indifference of the various occupiers left plenty of room for parallel structures and banditry.

The Murgia hinterland had long been densely forested, and there was little road network apart from the main communication routes, most of which were antique. Depending on their interests, the gangs were also used by the local feudal lords to suppress rebellions and collect excessive taxes. On the other hand, some bandits received enormous support from the population when they specifically turned against occupying powers and rich lords.

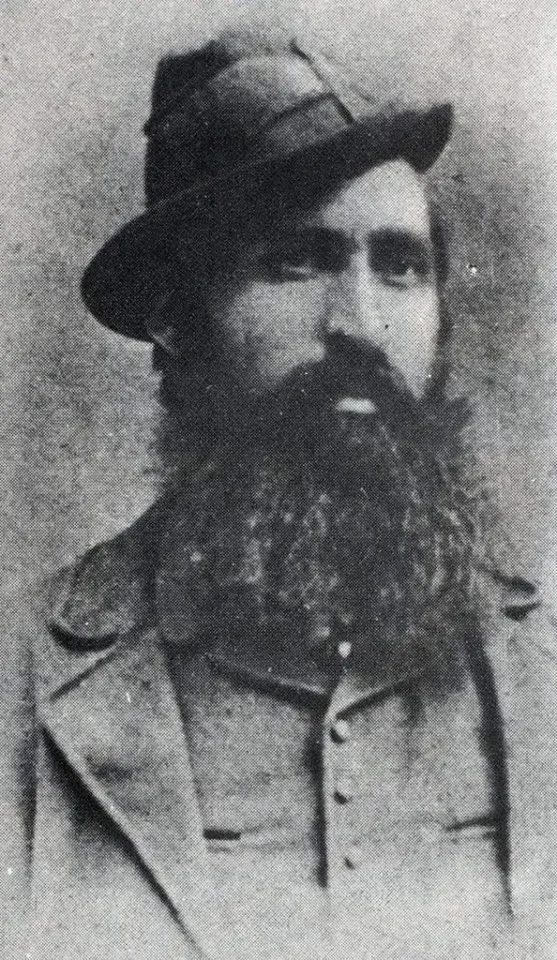

Carmine Crocco, 1830-1905, Brigand leader with the myth of a folk hero

Photo: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

In particular, after the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy, former supporters of Garibaldi turned to guerrilla warfare against the new state. Disappointment at the lack of improvement in living conditions, especially for the rural population of southern Italy, and the extremely cruel actions of the royal soldiers against the rebels led to a sharp increase in the number of brigands in the second half of the 19th century. To this day, many of them enjoy a mythical cult status despite their equally brutal actions.

Neglect and the resulting anarchic, completely opaque conditions certainly contributed to the fact that for a long time rural Puglia did not prosper, poverty remained high and, in the end, little has changed culturally, sociologically or structurally.

The high walls that surround every farm, every citrus orchard and every small village are also evidence of this constant insecurity.

From today’s perspective, we are pleasantly surprised at how faithfully the old towns, villages and masserie have been preserved, without the terrible disfigurements of modernity that are so prevalent in northern Europe. We should not forget, however, that until not so long ago it was above all poverty that forced people to live in such seemingly archaic conditions.

Michelina de Cesare, 1841-1868, confessed „Brigantessa“

Photo: Unknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Completely surrounded by high walls – Bambarone La Villa

Photo: Stefan Schneider

The valuable citrus gardens were also walled in and enclosed – Bambarone La Villa

Photo: Stefan Schneider

Puglia during the two world wars of the 20th century

The end of the First World War (in which Italy fought on the side of the Entente, the victorious powers) in 1919 triggered a serious national crisis, which led to the rise to power of Benito Mussolini’s Fascist Party in 1922.

In the two years before, Puglia had already been the scene of murderous and widespread attacks by the fascist Blackshirts. The intimidation and violence, which they called the fight against socialists and trade unions, brought Puglia under fascist rule with the support of the local landowners.

Although there were no extermination camps in Italy, there were many concentration camps, which were only a temporary stop on the way to certain death, especially for Jewish prisoners. In Puglia, there were concentration camps in Alberobello, Gioia del Colle, on the Tremiti Islands and in Manfredonia, which are still little known today.

Mussolini wanted to secure his power internally by means of large-scale infrastructure projects. In Puglia, this meant in particular the creation of new cereal-growing areas through drainage and irrigation systems. New villages were built from scratch to facilitate the settlement of peasants, while in the cities, monumental public buildings and road systems in the Fascist-style were erected without any reference to regional and historical structures.

Italy’s sometimes ambivalent relationship with its history during this period may also be due to this massive modernisation of previously extremely underdeveloped regions. Italy was spared widespread bombing, and there was no real ‘zero hour’, either from the occupying powers or from internal forces.

From 1936, Italy became a close ally of Fascist Germany and an active participant in the Second World War. Only the Allied landing in Sicily in 1943 brought about the fall of the dictatorship (except for a remaining fascist part in the north) and Italy changed sides in the war. In 1946, after a referendum, the monarchy was finally abolished and the Italian Republic proclaimed.

Casa Rossa in Alberobello – one of Puglia’s concentration camps

Photo: Valeria.Buonpane, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Caserma C. Bergia in Bari, built in 1932

Photo: https://www.artefascista.it/

Economic development since the post-war period

Even before the Second World War, only about 17% of Italy’s industrial workers were employed in the south, and a much higher proportion of industrial plants were destroyed during the war. After the war, the country was still predominantly agricultural, although yields per hectare were significantly lower than in northern Italy. This was due to the large proportion of large landowners who did not live on their land, but only leased it and did not look after it.

Before 1950, 19% of all municipalities in the Mezzogiorno had no water supply, 40% no sewerage and many no electricity. 24% of the population in the south were illiterate, due to the totally inadequate educational facilities.

Between 1950 and 1970, sweeping land reforms, structural measures such as irrigation, road and railway construction and financial aid brought about a real upturn, but apart from this period, the gap between northern and southern Italy has widened rather than narrowed since the unification of Italy in 1860. The close links between politics, business and organised crime that came to light from 1992 onwards further paralysed the country.

Peasant women in Puglia 1954

Photo: Touring Club Italiano, Creative Commons

Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International, via Wikimedia Commons

In recent years, however, Puglia has seen a very encouraging development: the economy is growing, thanks mainly to the increase in agriculture and tourism. A high-quality fashion industry has developed in Salento, producing for well-known luxury brands. Puglia even leads Italy in the production of open field vegetables and the number of wine producers. It is to be hoped that the decades of emigration can finally be halted and that young people in particular will see a positive future in this beautiful and rich part of their country.

The delayed economic development of the past offers great opportunities – intelligent, profitable tourism for all, in harmony with historical structures and nature, the development of infrastructure in an environmentally friendly manner, the use of the latest technologies in the conversion to renewable energy sources and, last but not least, a return to Puglia’s heritage as a melting pot of European, Middle Eastern and North African cultures, with every reason to be proud of this land with such a unique identity!

Matera, Photograph taken between 1948-1955

Photo: National Archives at College Park, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Coast near Torre Sant Andrea in Puglia

Photo: Giuseppe Milo, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Old port of Monopoli

Photo: Acquario51, CC BY-SA 4., via Wikimedia Commons

The ambition of Bambarone La Masseria

We approached and discovered Puglia with great respect and admiration. And it is with this attitude that we have tried to bring the ancient walls of Bambarone La Masseria back to life. Carefully adding new elements and at the same time making the old visible and tangible: this was our idea and our aim in planning and renovating this Masseria.

We invite you to come and see for yourself the charm of the historic vaults, the grandeur of the centuries-old olive trees, the scent of lemon blossoms and the aromatic maquis. If we have piqued your interest, you can book your own Puglia experience here.

Henriette Schneider

8.4.2025

Spring in Bambarone La Masseria

Photo: Stefan Schneider

Room Il Fienile in Bambarone La Masseria

Photo: Stephan Braun

Sources for the blog ‘A journey through the history of Puglia’:

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gioacchino_Murat

https://www.diocesiconversanomonopoli.it/diocesi/

https://www.provincia.brindisi.it/index.php/storia-e-tradizioni/i-comuni/fasano

http://www.brundarte.it/2014/10/30/lama-dantico-fasano-br/

https://erenow.org/common/an-armchair-travellers-history-of-apulia/36.php

https://www.patrimoniomondiale.it/?p=68

https://library.fes.de/gmh/main/pdf-files/gmh/1960/1960-09-a-545.pdf

https://www.preistoriainitalia.it

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geschichte_Apuliens#Das_normannische_Reich_in_Unteritalien

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erster_Kreuzzug

http://www.osservatoriooggi.it/vivi-fasano/guida/72-le-masserie-fortificate

https://www.pugliain.net/la-puglia-fascista/

https://www.pugliain.net/fascismo-faceva-bella-la-puglia/

Guida al Museo “Museo Nazional Archeologico die Egnazia “Guiseppe Andreassi” “; Quorum Edizioni – Bari 2015, Terza edizione settembre 2018

Schede degli Ambiti Pesaggistici; Ambito 7/ MURGIA DEI TRULLI (schema di PPTR)

PPTR Allegato 6 – La “Storia” per il piano